Spotlight: Akshat Nauriyal (Yesnomaybe, St+Art, Now Delhi, Awaaz)

13 October 2022

Around 350 monochromatic portraits were plastered across the external walls of the warehouses lined up on Mumbai’s nearly-150-years-old Sassoon dock. They overlooked the hectic rhythms of the fish market below, wafting in concentrated doses of the smell that is part of almost everyone’s experience of the seaside city.

In a population more used to having the faces of movie stars plastered across its streets and public spaces, Akshat Nauriyal’s co-created (with Pranav Gohil) array of portraits on Sassoon Dock pushed back on it by giving the limelight to the docks’ primary community and Mumbai’s earliest settlers: the fisherfolk.

“To be able to speak to people, learn about their communities, sensitise myself about their dynamics, and then be able to bring that into the project was the most important takeaway for me,” says the New Delhi artist of capturing and exhibiting those portraits in 2017 as a contribution to French artist JR’s global participatory art initiative ‘Inside Out’. By making the fisherfolks the subject of the portraits, convincing them about the work, capturing their likeness with a pop-up photo studio and then plastering the stylised results across the space that they define, Nauriyal and his colleagues highlighted the predominant trinity of Koli, Hindu Maratha and Banjara communities.

Inside Out at Sassoon Dock

“To bring the voices of people that are usually not heard from, or stories that are left on the wayside by the mainstream – those define the projects that I am always interested in”, explains Nauriyal as the mandate that drove his effort at Sassoon dock and his wider body of work. That body of work includes co-founding St+art, the collective and platform now widely celebrated for galvanising the undercurrents of street art in India by transforming localities like New Delhi’s Lodhi Colony and Shahpur Jat and creating India’s largest as well as tallest murals; documentaries capturing the capital city’s underground sub-cultures; socio-political stance-charged Instagram filters that examined social media platforms as a space for activism; short films tracing music-driven activism in different countries; music acts ranging from Another Vertigo Rush and Teddy Boy Kill to Hoirong and Yesnomaybe; and currently, an ongoing project that keeps Irom Sharmila (famously known as the ‘Iron Lady Of Manipur’) at its centre while it inquires into the cost borne by the leader of a movement.

Whether music, film, augmented reality or paint-based, the New Delhi artist’s efforts carry an easily notable sub-layer of activism, which has founds its necessity rooted as far back as he can remember.

Early Beginnings

Coming from a military background, Akshat was privy to the slow cogs of government offices which worked its way into disillusionment with the system around the time he developed his initial interests in arts and culture. He recalls sitting stunned listening to tracks by the likes Rage Against The Machine after downloading them off of Napster at the cusp of Indian households getting connected to the Internet and finding his thoughts make cohesion within the activist lyricism of the band and similar angsty associates.

The result was a deep-seated formative ethos that leaned towards art that stands for change and of having ready access to it. An ethos which was held back from getting showcased, save for through the array of rock bands that he drummed for during his school and college, while he navigated through the most common education pathway of engineering degrees and college placements prescribed to middle-class Indian kids. Eventually and gradually course-correcting himself with a move towards filmmaking and work for NDTV’s ‘Almost Famous’, Akshat started venturing out on his own around 2007 and 2008.

Now Delhi

“Because of being involved with the music scene, I was involved with a whole bunch of creative people from across the spectrum. Art galleries and things usually have a specific kind of people coming to them, but I’ve found that music is quite open in terms of the kind of audience it draws,” says Akshat. “Through that experience, I started seeing this other side of Delhi which I hadn’t experienced before I met these performance artists, digital artists and all kinds of artists who were the same age as me and were trying to push the envelope.”

Making these artists the focus of his first major venture as an independent filmmaker, Akshat, who often works under the pseudonym Tahska, established ‘Now Delhi’, a film studio now synonymous with a run of short documentaries it generated on the likes of street artists, B-boys, extreme metal groups and rap cyphers in the capital. “At that time, you could still say that there was this underground – an underbelly that Delhi had which nobody was talking about in the mainstream media,” he continues, expanding upon his comparison of a city to a living breathing thing defined by the people that it in turn influences. “‘Now Delhi’ delivered an exploration of that. It was an exploration of all the different kinds of subcultures that exist in the city, and also how the artists are responding to the city itself.”

The films exposed a running motif early on – one of prioritising the question. Akshat carries strong openings and convictions, but they remain held back when he is behind the artistic lens to allow for the audience to do their own thinking. The ‘Now Delhi’ film on Khirkee Extension, a collective effort of street artists to create art around the namesake South Delhi locality, presents the artists reflecting on the economic dichotomy of the neighbourhood and how it inspires their art. They retell how the kids kept engaging with the creation process of the murals before the documentary ends with the local elders frustratingly venting how they don’t get the purpose of this art and its messaging. The film invites the viewer to ponder over the significance of the street artists’ efforts and their relation to the residents of the locality.

“It’s something that I’ve tried to carry forward with all my work,” explains Akshat. “It comes from being able to first understand what the people who actually I’m trying to talk about feel, rather than impose my preconceived idea of what they might want to talk about.” For all the films of ‘Now Delhi’, Akshat first became a part of the sub-cultures he was highlighting or a close associate before micing them up. A decade later, with his current subject being a national icon like Irom Sharmila, he is tagging along to observe her usual going-abouts to discover the narrative naturally instead of imposing it. “I’ve always been a fan of gonzo journalism, like Hunter S Thomson and his writing – in terms of just immersing yourself in a situation to truly tell the story.”

St+art

Being close to his subjects meant Akshat had become a close associate of the street community of India, having made them the focus of ‘Now Delhi’ multiple times. Sharing a studio with one of its proponents, Hanif Kureshi, he soon found himself teaming up with Arjun Bahl, Giulia Ambrogi and Thanish Thomas to create the five-piece team that would become the founders of St+art.

“There was an initial conversation about doing a festival, which we did without having any idea that it [St+art] would become this behemoth of an organization,” Akshat recounts the early days of the organization with the festival bringing together the artists to Shahpur Jat and its founders being hands-on with everything from moving the ladders and bringing the paints to Nauriyal documenting the process. “It was a logical progression for ‘Now Delhi’ to transition to St+art India,” quips Akshat, noting how the documentaries took a backseat as the workload got higher and allowed him to honour his formative drives of making art accessible while exploring a city and the many narratives it homes.

Within a few years, St+art became a go-to organization for cultural consulates and medium to big brands, creating local landmarks across the country and transforming neighbourhoods, especially in New Delhi and Mumbai. The former’s Lodhi Colony remains defined by the makeover given by the collective during its annual festival. It was the place where St+art was fully able to realize its early motivations of creating art that was available to all and integrated all – specifically, through participatory murals, singing workshops, painting workshops and the like. Yet as the organization became a brand in itself, the ship started to feel too big to steer into radical corners – which Akshat still longed to address.

“The initial years of anything are the best. They're the most honest. They're the most genuine. They're the closest to the vision that you start with. As things get bigger, there comes a set of compromises that one has to start making. I think that's the nature of anything that becomes big after a point of time,” he concludes his around half-a-decade-long journey with the prominent street art collective.

Yesnomaybe, Augmented/Virtual Reality

As St+art began to fade out from his professional life, his other continuing artistic efforts began to appear more prominently in the limelight again. Adding another feather to the musical cap, Akshat debuted his solo moniker Yesnomaybe, an outlet where he brings together all the facets of his work as marries the retrofuturism of synth-rock with the futurism of interactive filters and augmented reality-driven films. The latter also becoming a device for Akshat to continue posing topical questions while creating work that stood for something.

2019 was a particularly politically-charged year for India: BJP, the country’s right-wing majoritarian government, was re-elected to power with a higher parliamentary presence; it used it to abrogate Kashmir’s special status; and introduced the discriminatory Citizenship Amendment Act which faced nationwide protests that were met with controversial police violence. With augmented reality, Akshat offered tried to offer a response for all of it: a filter fashioned after prime minister Narendra Modi that let out the word “lie” every time you open your mouth, headers stating stances on Kashmir and CAA, and, for the following year’s state elections in Delhi, an interactive quiz where you can nod or shake your head based on who you’re voting for.

“I felt social media platforms are almost like the new town halls where people are coming and discussing things. It was an interesting space to explore to try and also see if I could create work that could help on ground movements and also get people involved more than just changing a display picture,” says Akshat. “It was honestly a social experiment.”

Within days, around a million people saw the multiple of the filters. The mode of activism was talked about by the likes of Al Jazeera, attracting loud pro-government commentators to Akshat’s profile alongside concern for safety by well-wishers. The work definitely rattled a few minds and sparked newer questions in Akshat’s own. “I started a conversation about what use it actually played in society. On my Instagram Stories, I asked people the question, whether they thought that it was just armchair activism or whether it actually led to any kind of change,” he remarks. Alongside equal amounts of opposing viewpoints, the “social (media) experiment” also saw its second phase as the platforms began, in most cases, a silent clampdown on politically-charged use of its platform. The traction for the filters and their related posts began to go down and, as is currently being highlighted in courts, the platforms themselves had to cater to clampdowns by the government. “It was also quite disillusioning, because the same platforms, which are supposed to be platforms for free speech are the ones that ended up censoring you,” reports Akshat.

Awaaz

With censoring becoming more and more obvious and Instagram itself pivoting from a creator-friendly platform, Akshat moved his exploration into creating meaningful work and examining the modes for it to other outlets: installations, talks and, coming a full circle, to films again. As part of Goethe-Institut’s ‘M.A.P // A.M.P’, the filmmaker created a series of documentaries entitled ‘Awaaz’, turning the lens yet again to underrepresented artistic voices. Handpicking with the help of research and local social networks, ‘Awaaz’ highlighted politically outspoken artists from India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Iran to look at the history of protests from these countries.

“Anytime you go on Twitter, somebody is getting boycotted. We’re living in an age of outrage,” says Akshat, noting how any political discourse is getting mudied up online by internet trolls while a work of activist nature doesn’t get platformed enough outside it. Allaying that, ‘Awaaz’ unearthed the nature of dissent specific to each country – whether it was about signalling the erosion of administrative infrastructures and economy in Sri Lanka, which erupted within weeks of the film getting released, or the difficulty in finding a voice that can publicly speak against the powers that be in a country like Iran. “There was a responsibility that I had on my end which was to ensure that I don’t put out content that can eventually lead to trouble for them [the artists],” continues Akshat. “Which is why I did in a way where we were actually chronicling the past protest movements to give context of where the country is right now, rather than attack any of the present figures.”

Even with the varying specifics, much like M.A.P // A.M.P’s crowdsourced repository of protest music, ‘Awaaz’ brought out the parallels between artistic activism around the world, signalling a unification of voices and the possibility of shared empathy. According to Akshat: “[The films] platform these movements in a way so that other people in other parts of the world can see that we’re all pretty similar and that there is merit to creating work like this.”

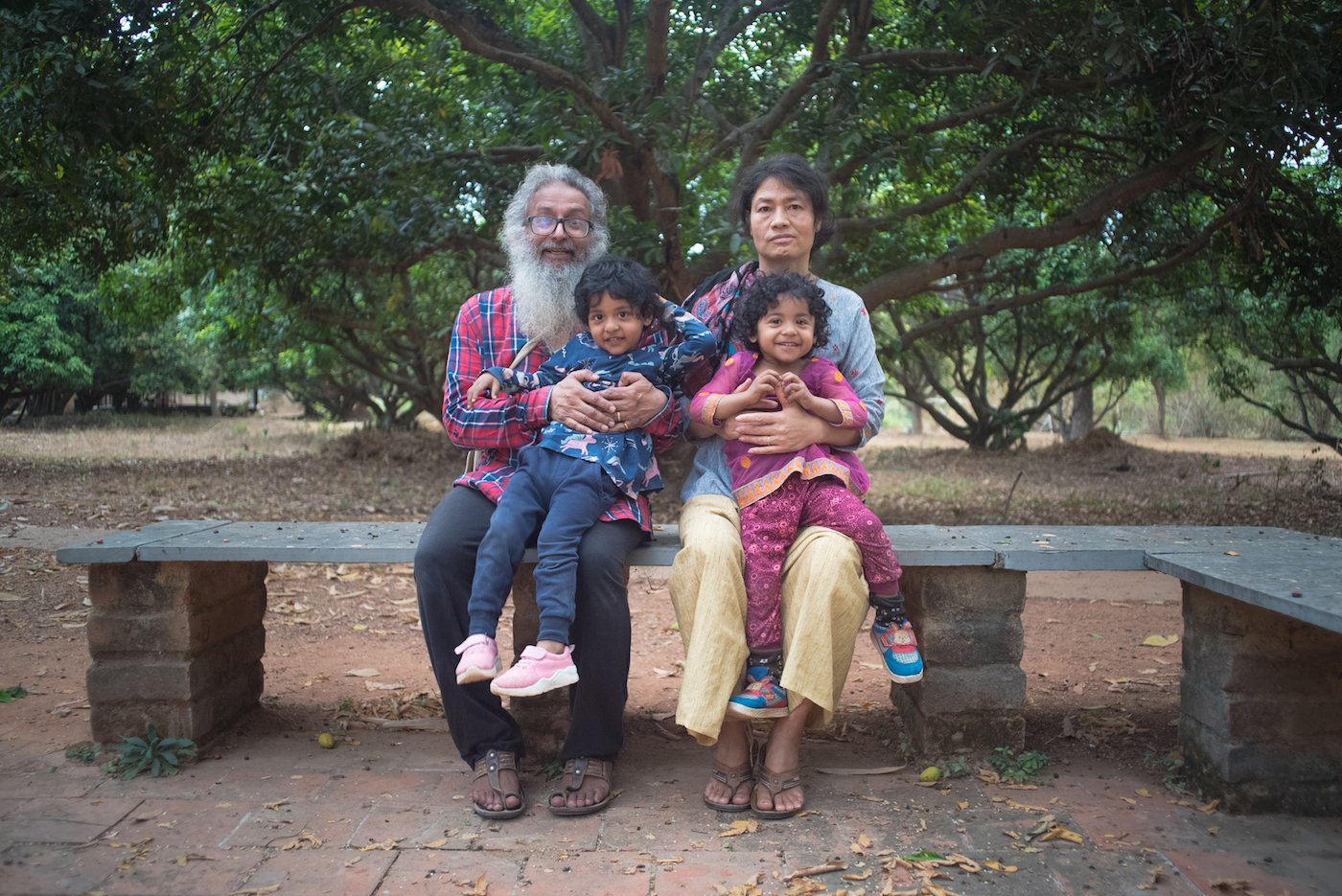

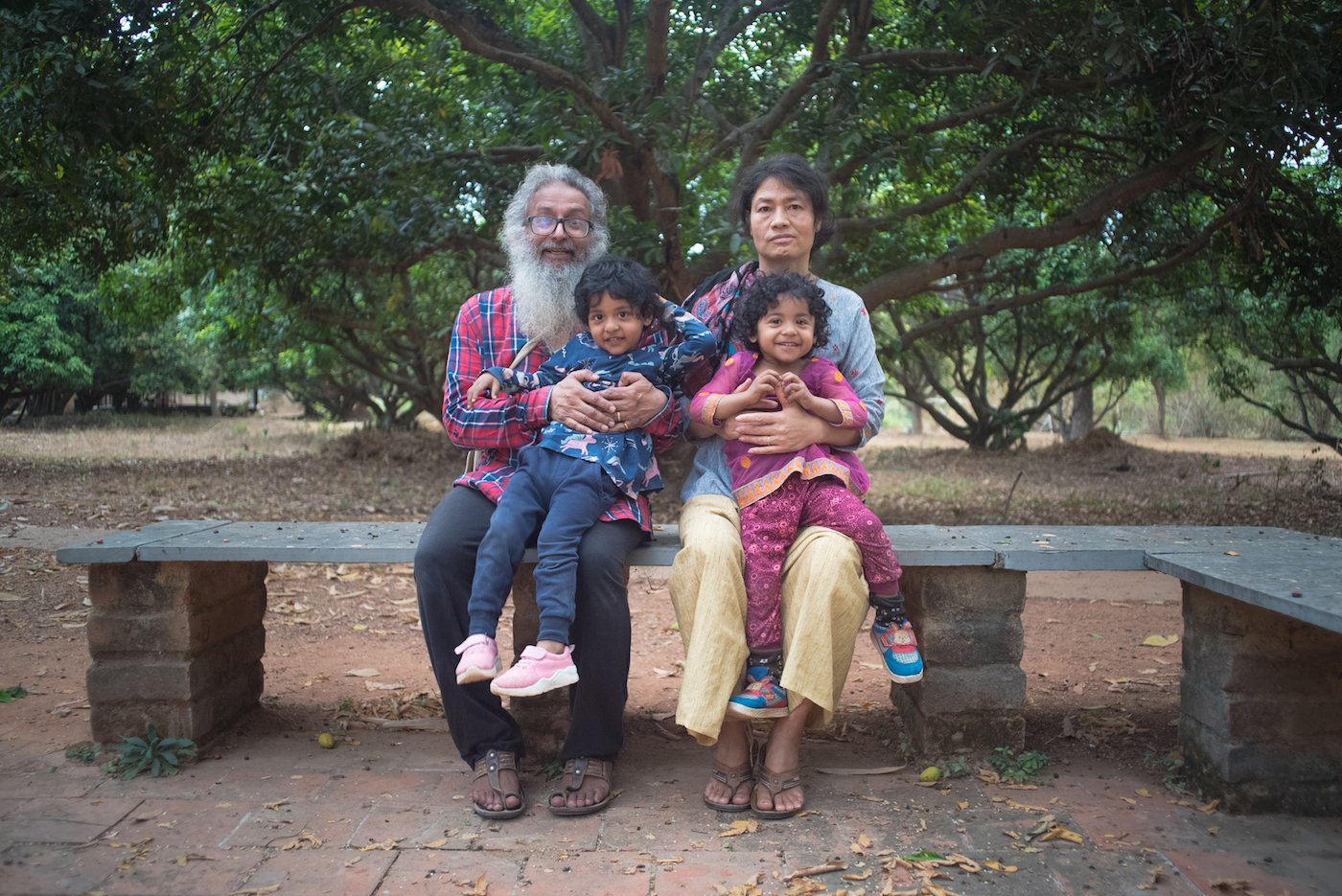

Irom Sharmila with family by Akshat Nauriyal

“I feel a cycle has finished and a new cycle is beginning,” he adds as we agree on how the films on national sub-cultures with ‘Awaaz’ feel like coming a full circle in light of how films on Delhi’s sub-cultures with ‘Now Delhi’ kicked things off. Since finishing ‘Awaaz’, two of the countries Akshat turned his lens to have been taken over by protests, which have emerged out of the shadows to engulf the streets, at times, fulfilling predictions touched upon in the films. Meanwhile, Akshat has moved on to creating the new chapter for Yesnomaybe and shadowing Irom Sharmila, not just documenting the cost her struggle for fairer civil rights has demanded but also building a multi-faceted reflection of her poetry and personality. For the New Delhi creative, the parallels and narratives to be unearthed by his personal artistic vision continue to draw him to the margins.

.

.

Word by Amaan Khan

Profile image by Akshat Nauriyal