Compassion, Collaboration & Acceptance: How Music Collectives In Asia Are Forging New Paths For Artistes

22 April 2022

The creation and nurturing of a ‘community’ through music collectives have given rise to some of the most powerful social and cultural movements in South Asia. While some strived to construct a space for artists beyond the conventions of mainstream culture, others offered a safe space for dialogue on prevalent issues including discrimination, social injustice and cultural diversity. Such collectives have played a crucial role in organising artists from diverse backgrounds by offering a ground where varied artistic explorations could co-exist. We strike a conversation with some of the collectives in the region and understand in depth how their journey helped pave the way forward for a generation of artists.

“A musical community can be socially and/or symbolically constituted. It does not require the presence of conventional structural elements nor must it be anchored in a single place although both structural and local elements may assume importance at points in the process of community formation as well as in its ongoing existence”: writes Kay Kaufman Shelemay in her essay Musical Communities: Rethinking the Collective in Music.

She suggests that attention to processes of descent, dissent, and affinity both elucidates music’s generative role in shaping new collectivities and unsettles the notion of music as a static sonic marker of social groupings. “Rather, a musical community is a social entity, an outcome of a combination of social and musical processes rendering those who participate in making or listening to music aware of a connection among themselves. Within collectivities shaped by processes of descent, music moves beyond a role as symbol literally to perform the identity in question and serves early on in the process of community formation to establish, maintain and reinforce that collective identity,”Shelemay says.

On January 6,2018, amidst chants of Jai Bhim, the Casteless Collective – India’s largest ensemble political band – gave their first performance in Kilpauk, Chennai.Comprising a myriad of genres from rap and rock to Gana (a form whose origins lie in funeral music; it is accompanied by percussions that are socially associated with the rhythms of the graveyard), the ensemble – whose name is inspired from 19th century anti-caste activist and writer C IyotheeThass’s jaathiilladhatamizhargal — since its inception has garnered attention for their lyrical prowess as they shed light on social issues including caste-based discrimination, honour killings, Dalit assertion and rights of the LGBTQ+ community.

“With his work not only did filmmaker Pa. Ranjith disrupt the mainstream film industry but he also enabled disadvantaged and sidelined arts and artists. Through this process, he started making waves within the arts community. For his next venture, he hoped to use music as a medium to create strong ‘Dalit-assertive and social justice’ content,” says Tenma the band leader of the collective, “And, I was trying to bring the arts and music community together to build a conscious and ‘equal’ music ecosystem in Chennai through my collective (Madras Indie collective). We met and discussed what we wanted to do. He then introduced me to some Gana singers who had performed earlier at a photo exhibition titled Nanumoru Kuzhanthai. He asked me to train them and create a band. The philosophy of our journey is to use this medium as a collective and bring out conversations which were ignored, and to educate the masses of what being equal is about in a society divided by caste, religion and class. The vision is to unite everyone through music but also acknowledge the existing social demons and defeat it.”

Image courtesy of The Casteless Collective

Image courtesy of The Casteless Collective

The Casteless Collective is a combination of various sonic acts coming together. Their sounds are an ode to Chennai’s Dalit community. There is the Gana group – Gana Muthu, Gana Balachander, Isiavani, Chellamuthu and Dharani who also specialise in folk songs. The rock band comprises of Sahib and Manu who are well-versed with jazz and blues traditions. Apart from the traditional funeral-musician combo of Gautham and Sarath, Arivu and Nandhan’s mastery over folk and contemporary pop has amassed considerable praise across India.

“As the composer and band leader of the collective, I had to bridge and write these melodies and compositions keeping in mind the sonic sensibilities of various personalities as well as traditions. We are also exploring some new methods in our arrangements which involve collaborations with other artists. Only time will tell how we reshape our sound. Art should be used as a catalyst of empathy to honour humanity,” says the artiste who further explains that the bottom line of all of these movements or conversations – social, political or artistic — should lead us to discover compassion, unity and a sense of acceptance within ourselves, “Throughout the process making music for the collective, I felt a sense of self returning; a sense of who I am and what I need to do. When I go back in time during my initial days as a musician and most importantly as a bass player, I remember being exposed to black musicians who played funk, disco and jazz. I read their stories, watched interviews and understood how their culture and lifestyle is so intertwined with the music they made. Music is such a personality-driven art form and most artists are always on the pursuit of their ‘self’ if they want to make original music. It’s a truthful communication with the medium itself.The response from the medium because of the message you are giving takes you to a better consciousness, and makes you humble.”

In conversation, Tenma shares how empathy and collaboration helped them address the numerous challenges that the collective faced and also enabled musicians to craft their artistic journey together. The global pandemic brought forth a crisis within the music industry all over the world. Owing to safety regulations and restrictions, the collective’s jam rooms had to shut shop. And, the uncertainty is still prevalent as far as live performances go. “Collectives are finding it difficult to manage since as a country we don’t have a lot of spaces to perform. We are using this time to build our own path. Pa. Ranjith has been the main producer of our shows. One of the most important things that need to happen to make any sort of fundamental change for artistes in this landscape is unity,” he says.

In the last two years, while many collectives went on an extended hiatus during the unprecedented crisis, Jwala that remained dormant for a while resurfaced in the midst of a raging pandemic. Founded in 2017, the Indian artiste collective and record label has released over 70 songs through 11 compilations featuring more than 65 artistes so far. “When we made this collective, we were young and studying in college. We had plenty of time to invest in nurturing Jwala. However, it’s not the same anymore. It has been 5 years, and a lot has changed in our lives. Jwala has taken a back seat, and we are okay with it! We’re proud of the work we’ve done and will continue to put out quality content whenever we get together. All of us have had different artistic journeys even though we are a collective. We worked towards making a support system for each other and the producers we showcased. There was a great peer learning involved since we come from different backgrounds and production styles,” say the artistes, “Each of us have our own individual paths. Our philosophy is to break the monotony in the music scene and bring new talent from all over the country regardless of the kind of music they make while also helping them showcase their talent in the best way we can. Jwala acts a catalyst for young producers by providing them with a community that supports each other and grows.”

Image courtesy of Jwala. Artwork by Himanshu Tokas

The artistes suggest that the commercial music industry in India is dominant and seldom supportive of independent electronic music. They believe that collectives can serve as flag bearers of a movement that can nurture unconventional sounds and musicians. “In the last two years, it became even more important for cross-collaboration between producers and visual artists from different parts of the country. The pandemic managed to catalyse these collaborations because the Internet was suddenly the only means through which this could be done.”

With the sudden imposition of lockdown, curfew and restrictions on gathering and movement, collectives across the country collaborated on focused explorations and worked towards charting a paradigm shift in observable cultural practices and artistic processes. “Being in a collective has helped us deal with our problems in a more creative manner. We were taken aback by the restrictions and at one point it felt as though it was never ending. However, we have released more music in the past one year since our inception,” says Mrinal Paul who goes by the moniker MOKSH and founded the collective Movement of Expression (MOX). Since 2017, they have been curating hip-hop events in and around Meghalaya. This is the only rap collective whose crew features Bengali, Assamese, Nepalese and Khasi rappers.

Voices from the North-East part of our country are seldom heard in mainstream discourse whether it is art, music, literature or even politics. Unemployment, poverty, fading language and diminishing identity, migration, rampant drug abuse, and racism — these are some of the issues that artists from the collective have been sharing their opinions on apart from casting a glance on the socio-cultural and political issues prevalent in the region and country.

Image of MOKSH. Photo by Ankit Ghosh

“We are diverse not just in terms of our language and views but also with our sonic explorations! At the heart of it, it is all about the zeal to create good music which caters to a diverse set of listeners. While various elements of hip-hop remain a major influence, we are still working on how to incorporate traditional sounds authentic to our region. I believe music is a rebellious art form. It reincarnates itself into new genres and sub-genres every once in a while. However, art or music alone cannot bring forth a social transformation but it can surely be a medium for propagation. As a collective, we are building an audio/visual archive which can tell unfiltered and uncensored stories of our times,” says Mrinal who also reveals in conversation that they are a bootstrapped entity, and mostly fund their own projects. “Getting people to invest in our vision has been a challenge from the start. So, finding a market for our work has been a herculean task! Pandemic got us multi-tasking. We have seen a rise in enquiries for commissioned/commercial work but that is not enough to fund our ambitious creative projects. We are now looking at creating multiple revenue streams and not just rely on events, brands or IPs alone,” he says.

Breaking barriers in art and sound

Although many music collectives may have dissolved, disbanded or faded over time, their immense contribution towards building a community cannot go unnoticed. In the process of nurturing something extraordinary while battling terrifying circumstances, they played their part beautifully. Today, there are many more underground collectives as well as artistes who sought inspiration from such ventures and are continuing to break new barriers in the realm of both art and sound.

“There aren’t many music collectives here in Nepal,” says Rajan Shrestha (Phatcowlee), Kathmandu-based inter-disciplinary artist, “2000-2010 saw a prominent wave of heavy metal music… mostly underground. Most of the practising professionals today are a product of that scene including my own band Jindabaad whose members include Abhisek Bhadra (keyboards) who also heads the Kathmandu Jazz Conservatory, Rohit Shakya (vocals/guitars) who leads Fuzz Factory Productions and has a recording studio, Sunny Tuladhar (guitars) who is a luthier and has his own custom brand of handmade electric guitars and basses, and Kiran Shahi (drums) who is involved with jazz education through his own school. However, the situation now is different. There has been a great development in the number of venues where music can be hosted. The quality of sound systems too has exponentially improved, and we have witnessed a policy level development in institutionalised music education in Nepal.”

In 2015, Rajan co-founded Fuzzscape along with two of his friends Prasiit Sthapit (photographer/filmmaker) and Rohit Shakya (music producer/director). It is a multimedia project that involves a team of creative professionals travelling to explore the artistic culture and society of Nepal. They collaborate with artists from different communities to develop a body of work inspired by their interaction with the people, the space, and its culture. What started as an experiment has now grown into a documentary series about the process of collaborative music-making, and an online multimedia archival project. They have also been facilitating workshops on intangible heritage, issues surrounding it and its conservation through multi-media.

Image courtesy of Phatcowlee

“Also, along with Daniel (other half of Anaasir — an electronic duo that we formed during an art residency in Kathmandu) and Manal (a Maldives based electronic musician/DJ), an electronic music festival called ‘Sine Valley’ was started in 2016/17. It was a brainchild of these two artistes. Since the ‘community’ here is small, and the logistics of Daniel flying from Pakistan and Manal coming in from Maldives proved impractical, we couldn’t pull off hosting the festival in Kathmandu for more than two years,” reveals Rajan.

Since 2019, he has been a part of a grassroots music festival known as Echoes In the Valley. The organizers consist of event managers, ethnomusicologists and musicians who are striving to bring access to music both old and new to the masses through performances, festivals, workshops and residencies. They have also just started a research and archive wing Nepal Music Archive. “Last year, we did (still ongoing) an online edition for 2021 edition of the festival. The performances were titled A Letter Home where we featured musicians from Nepali diaspora who are living abroad. It would have been impossible to bring them all here physically, logistically speaking. In a way, the COVID crisis made us think about this idea and it all worked out. We have also been conducting online workshops and confluences as a part of the festival. So, collectives and such festivals seem more relevant for the scene to develop or at least sustain it especially while dealing with the pandemic,” he says.

Intersection of technology and art

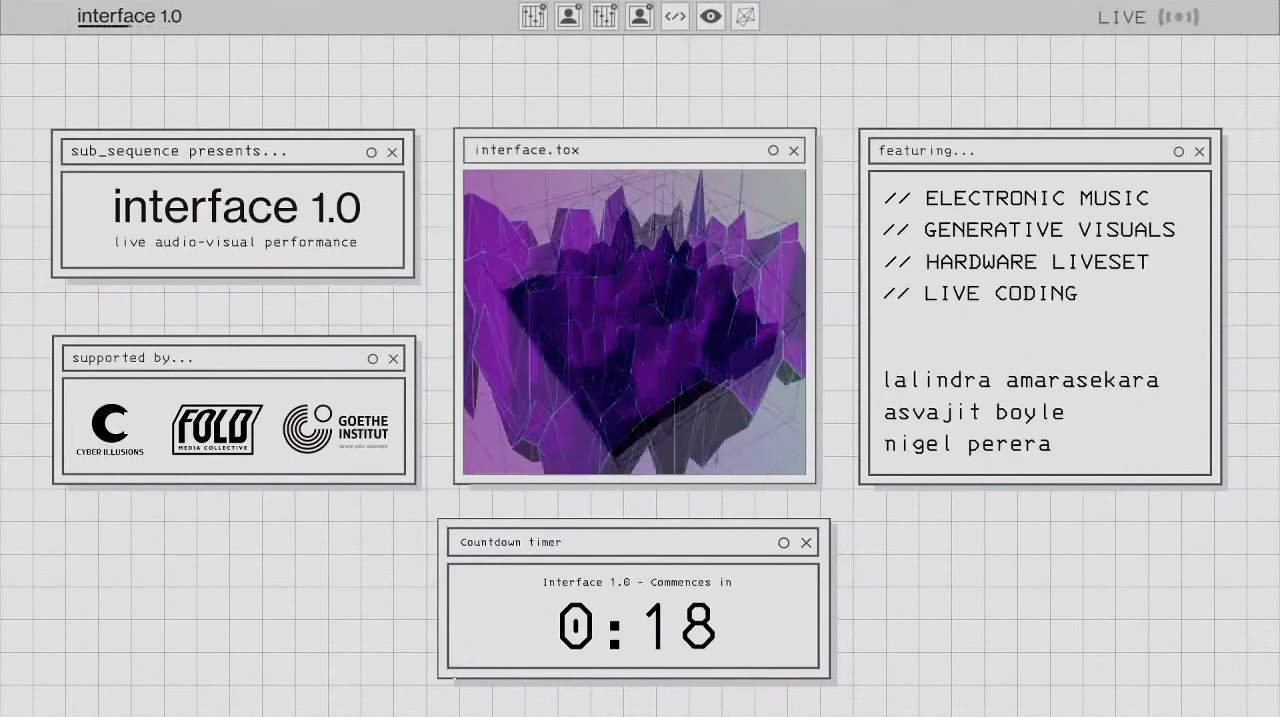

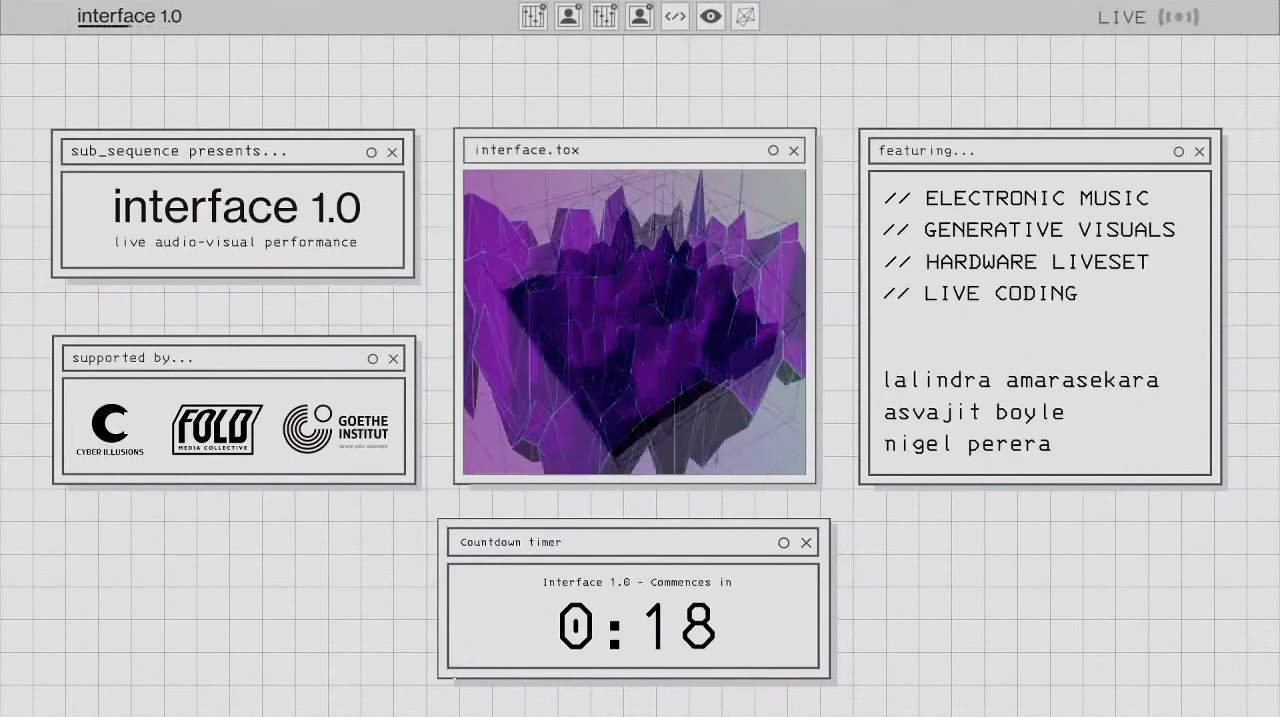

When Asvajit Boyle — electronic musician, audio-visual artist and designer based in Colombo, Sri Lanka – who is also the founder of Jambutek imprint and Foldmedia first started making music in the late 2000s, Sri Lanka was a very different place. “One of the most important aspects of musical development is collaboration and discussion with one’s peers. In a relatively small town setting like Colombo, stunted by decades of civil war and mismanagement, these can be hard to come by for those whose creative pursuits go against the grain,” he explains, “There was no scene for original electronic music here. There was no one to learn from and engage with. And, I felt the impact of that on my own personal artistic growth. Providing this support system for young and aspiring artists is one of the main goals of all our projects,” he explains.

In the initial months of the pandemic, the artiste along with his partners noted that the response of many performers to restrictions on public gatherings was simply to stream their performances live. “These types of performances attempt to translate the experience of a public event directly to a digital one and are often received as pale imitations of the real thing. Attending a concert or club night is not just about the performance. It is what it is because of social interaction and the experience of physically sharing a space with other human beings,” he says. Keeping this in mind, the concept for INTERFACE was developed. Their goal was to create a performance format that did not try to emulate a real-world event but rather embrace the aesthetics and limitations of its digital nature. This abstraction of a live performance allows viewers to engage with the performance on its own terms without drawing comparisons between physical events.

Image from the opening screen of Interface 1.0 by Sub_Sequence. View the full performance here.

Interface explores the intersection of technology and art as well as the potential for meaningful expression in the virtual world. After a live coding based introduction, the main event consists of a live hardware-based electronic music performance presented in the context of a computer operating system. “The two musicians are filmed using multiple cameras with their features blurred out using motion tracking tools. The music then triggers audio-reactive visuals. Each musical piece is accompanied by its own visualization and all the elements (which appear in windows) are manipulated in real-time to simulate the usage of an operating system,” says the artist.

Signifiers of socio-cultural change in society

There is no critical discourse around sound in Dhaka; no place where one can go for an education on the technology, business and social studies of music, writes Maliha Mohsin in her essay The Strange World Of Audio Engineering. She says structured programmes surrounding music technology have become absolutely essential to create more access to the field, and discuss even the business, ethics and politics of practising sound art in an industry where music has largely become an intangible, easily borrowed and saleable commodity.

In an attempt to engage with sound critically, Karkhana Collective — an initiative co-founded by Maliha — has been gradually working towards building a collective of artists and practitioners, thereby spearheading a movement that also addresses issues surrounding inclusivity, accessibility and identity. Through Ghurni — a series of listening and DJing sessions that does not limit itself to pure electronica and dance culture – they hope to explore how urban communities listen to music collectively.

Defining themselves as a sacred and supportive space for music, visual art, film, comedy and much more, initiatives such as Jongshon hope to perpetuate and nurture a holistic movement of art thereby altering Bangladesh’s cultural ethos. “We are a collaborative hub of artists that promotes rising local musicians — both individuals and groups — as well as aspiring entrepreneurs,” shares Pujan Goswami, the founder of Jongshon that serves as an umbrella for seven projects: Acoustica (music), Nondon (visual art), Greenventures (promotes a platform for green, eco-friendly and sustainable business to sell their products), Scene-e Night (Cinema), Fun- e Khan (Stand-up comedy), Shobdo-Kolpo-Brikkho (literature and poetry) and Udyog (showcasing young promising enterprises and its entrepreneurs), “And, each one has its own purpose.”

Image courtesy of Jongshon

Collectives have the power to reflect upon activities critical to the development of the community as well as carve a space for alternate sonic explorations and present them to a larger audience. It also helps set the precedent for new cliques to adopt best practices that will ensure that their music is heard especially in cities like Dhaka which does not have adequate infrastructure for music and creativity in general, says Khan Mohammed Faisal, the co-founder of Dhaka Electronica Scene and the founder of Akaliko Records that gradually evolved into an artist collective. “The creation of Dhaka Electronica Scene which is currently inactive was to merely address the need of a community for people who were still learning the craft. The idea was to have a democratized platform for artists to come together and try out new things including collaborations and learning,” he says.

In the last two years, several performing artists have migrated from urban areas as their income shrunk. Many lost their loved ones. Music collectives struggled, and artists braved newer challenges. “The pandemic changed everything. The few opportunities that existed before for new artists got taken away as money being spent on cultural activities dropped drastically,” reveals Khan Mohammed Faisal in conversation, “The lack of physical activity during the pandemic has also been detrimental to the scene. Overall, morale was hurt and instead of growth, we saw decline. For electronic music in Bangladesh, the craft and practice of electronic music itself acts as a signifier of socio-cultural change in society. The way the music is approached also tells part of the story where the case we are putting forward is how we can adopt electronic music as our own while being a part of the global sub-culture of electronic music.”

Sustainable and mindful programming

All cultural organisations at some point have faced massive barriers to growth owing to the lack of funding, poor law and order, corruption and the impatience to make money amongst other factors, says Raania Durrani. In 2015, she co-founded Salt Arts with the intention of cultivating new audiences for music and arts in Pakistan. Since then, Salt Arts, under her Artistic Direction, produced over 100 live, gender balanced and audio-visual/music ticketed public shows both in Pakistan and UK, and has worked with over 300 artists and creatives from Pakistan and other parts of the world.

“My work with Salt Arts was wildly inspiring in so many ways not only for me but also for the young people on the team as well as artists and audiences who saw the re-emergence of the public concert culture. It was like a light bulb had turned on, and a new wave of performance based businesses came into being: venues, ticketing agencies, artist management outfits and so on. The curatorial space in my opinion is still weak, and we have a long way to go,” she explains, “Festivals and shows are not made by one individual. They require deep investigation into culture and the understanding of human beings and their behaviour. I feel new platforms are especially in a rush; in a rush to be seen, to make money, to work with the biggest artists, to put up the largest possible shows, etc. I also strongly believe that the impatience of investors and lack of resilience are the greatest reasons why culture-based organisations end their work. Teams who win, win because of the momentum they build, and the chemistry they have achieved through resilience. Our work in culture does not thrive under pressure and unrealistic commercial expectations. That is just not how culture works!”

Currently based out of Hunza, Gilgit-Baltistan, Raania resigned from her role at Salt Arts in early 2021, and now works as a creative associate to Music Producer Rohail Hyatt at Frequency Media. Her work with The National History Museum and The Citizens Archive of Pakistan involves developing their digital narrative and strategy, stemming from the notion of diverse audience development, serving the youth of Pakistan. Apart from regularly consulting in the areas of cultural leadership (specialising in the South Asian space), Raania continues to curate shows independently while mentoring and furthering the voices of indigenous contemporary musicians residing in the North of Pakistan. This year, she says, her personal art — as an multidisciplinary artist and creative producer — is geared towards craft and technology, climate and culture.

Pivoting into the digital space

“I wouldn’t say that Pakistan has had a collective that is ‘truly’ experimental. However, collectives in the past such as Forever South definitely opened doors to experimentation given the wide array of artists on their roster,” says Daniel Arthur Panjawaneey who performs and produces under the monikers Alien Panda Jury and Kukido. The artiste has been at the forefront of Karachi’s underground music scene for over two decades. In the last several years, apart from playing bass for bands like Messiah, //orangenoise and The D/A Method, Daniel has also engineered and produced several records.

Image courtesy of Alien Panda Jury. Photo by Kittpong June Tangkamonkit.

“While most of the music I released on Forever South was generally instrumental, it gave me the license and space to add unconventional textures and noise into my sound that other people weren’t necessarily doing. The fact that Forever South existed and continued to do what it did for so long also helped everyone involved get on the international radar thereby enabling the collective to collaborate on residencies hosted here with international producers (Karachi Files). And, that encouraged everyone to experiment and find their own sound.”

Most collectives take the shape of labels or spaces. Some believe that they could bridge the gap between traditional labels and DIY. For instance, Cape Monze Records, a label that Daniel set up last year functions as both entities. “Everyone being there for each other and helping one another out; that’s what truly defines a collective,” he says, “There’s one collective that deserves a noteworthy mention! They are a group of young producers mainly from Islamabad and Lahore: Miracle Mangal. What I love about them is the frequency of content they put out. This is a great case study. They pushed themselves onto the scene quite early into the pandemic during lockdown, and made themselves accessible by hosting viewing and listening parties, and engaging with the community on discord. This not only helps new artists but also influences individuals who are considering pursuing art and sound.”

According to Daniel, the ongoing pandemic enabled artists and collectives to accept a new norm and pivot into the digital space where performers and audiences from diverse socio-economic backgrounds could partake in events. “It’s great especially in a place like Pakistan where it can be a herculean task to put a show together let alone be able to price your tickets so that you can make ends meet to cover all your overheads. In order to make a profit, one has to price tickets at 5000 PKR per entry which quite literally cancels out a large majority of the people from being able to attend such events because of a class divide. Online shows have leveled the playing field today.”

Tucked away in a narrow street in Karachi, The Second Floor (a coffee shop and community space) founded by Sabeen Mahmud offered a safe haven to many artists in Pakistan. It served as a collective space for musicians and also hosted numerous discussions on human rights, peace-building, environment, social development and poverty. T2F was instrumental in nurturing a space for artistes exploring diverse mediums as well as building a strong community. On April 24, 2015, shortly after hosting a panel discussion titled ‘Unsilencing Balochistan: Take two’ that shed light on the ongoing situation in Balochistan along with activists from the embattled province who voiced their concerns over missing Baloch nationalists Sabeen Mahmud was shot dead by armed assailants. Recording his statement before the magistrate, the culprit stated: “We shot her for holding a Valentine’s Day rally (…) When she sat in the car after her Balochistan seminar, I followed her and when her car stopped at Sunset Boulevard signal I shot her (…). He claimed there wasn’t one particular reason to target her; she was generally promoting liberal, secular values.

Image courtesy of Alien Panda Jury

“T2F was the first place I ever picked up a mic and sang a song on stage. Sabeen played an integral role in supporting artists and giving them a space to perform. A place like T2F existing at that time was an anomaly. I couldn’t imagine walking into a venue or a rentable space and saying I want to do a show here. And, the response was Okay, do it! No fees. Let’s just share the door sales 50-50 after you’ve covered all your rental costs for sound and lights. Everything that we earn will go back into T2F to make more events like these happen. That’s who Sabeen was, and that’s what the original T2F was all about. She didn’t care about the money. All she ever wanted was for everyone to have a voice and a place that enabled you to use that voice,” recalls Daniel, “Her death left a massive void that is still not quite filled. No one like her existed or exists today. T2F also reshuffled the way they function and formed a board that was mainly run by businessmen who saw it as a business. The place did however give birth to a lot of artists and activists — some of whom are still very active. On the other hand, her death also silenced a lot of people which is unfortunate because I honestly think she’d have wanted everyone to be their loudest.”

Art, the language of oneness

Faisal Rafi, one of the co-founders of Karachi-based Gangwar Studios, defines their venture not as a label or an organisation. “It’s a collection of artists from varied backgrounds who have come together to work on new music that none of us have discovered yet. And, that journey of discovery is unending. It’s infinite,” he says.

His journey leading up to the creation of Gangwar studios was filled with countless struggles. While Faisal was working on establishing the collective alongside his partner Ali Diwan, his wife was diagnosed with cancer. “She suffered a lot during those years, and unfortunately passed away. Hence, Gangwar studios became an even more important component of my life. It became a place for me to escape my emotional worries; a place for me to create new things, and a place to welcome others to create stuff with me, and without me,” he explains.

In conversation, he mentions how Karachi remains close to his heart, and how its distinct identity in comparison with the rest of Pakistan is rooted in its social and cultural ethos. Unlike other regions where cricket and Qawwali play a dominant role, Faisal tells us that the multi-ethnic and mutli-cultural neighbourhood of Lyaari makes it unique. “Residents of Lyaari are half-African and half-Baloch tribesmen. They are into football, boxing and hip-hop music. Lyaari personifies Karachi as a city. There are people from all over the region living there. In fact, the name ‘Gangwar studios’ is actually a pun. While construction of the studio was underway, we would sit on the rooftop and hear gunshots being fired,” he says and goes on to explain, “I truly believe that music and art plays a huge part in social development. This release that the people of Lyaari especially the younger generation have through music and sport is possibly the only expression they have. By expressing themselves, they become deeper and deeper entrenched in their culture. They become more vibrant. And, that’s one of the most beautiful things about Karachi.”

Image courtesy of Gangwar Studios

The philosophy behind Gangwar studios was to create a space in the middle of the old city away from affluent areas where most of the studios reside. Therefore, it offers a middle ground for everyone regardless of what strata of society they belong to. “It’s located in a place that is called the artist commune. We are not the only artistic space there. There’s an art gallery and even a customized clothing manufacturer. The whole idea was to be inclusive and not exclusive,” explains Faisal, “Our journey as a collective together has been very interesting because my collaborators – Ehsaan Bari, Humza and Ali – and I come from different backgrounds. We work on every genre you can possibly think of at Gangwar. Despite the hardships we experienced in the last few years due to the pandemic, we never really slowed down. We are welcoming many more musicians into the fold. We will just keep following the road and see where it leads us.”

Faisal believes that music is an abstract art. It keeps evolving. There isn’t a canvas to it for it is born out of silence. Just like art evolves, people evolve. It is the language of oneness. “I have seen people who don’t speak each other’s language communicate through music. I have seen fine artists who don’t even know each other’s culture work on paintings together. I have seen filmmakers and writers collaborate without knowing anything about the other person. And, that’s the beauty of art! If humanity as a whole can adopt that trait from art what a great world we will be living in where people would learn to overcome their own biases and accept one another.”

.

.

Written by Akshatha Shetty

Main Image by Madhavan Palinasamy of Tenma from The Casteless Collective

The article was originally posted on Border Movement on 07 March 2022

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of Border Movement and its partners.

Image courtesy of The Casteless Collective

Image courtesy of The Casteless Collective