An Unlikely Marriage: Indian Classical Music’s Century-Old Flirtation With Jazz

20 April 2021

I was recently asked if there was jazz in India, a question related to my life experience of 5 years living there. I received the question with a certain wariness almost as if I had to defend India from a colonialist or paternalistic position and explain to my interlocutor that, even if there was not a single jazz musician in India, this country was not lacking in a musical culture of equal value. Now, the good thing about jazz, as many of its protagonists understand it, is its permeability to other sounds and traditions following the logic of its own history.

Apart from the milestones achieved by the best-known Western musicians in the field of this cultural exchange, the question that seems to me to be less asked is: "Who are these Indian jazz musicians working on fusing indigenous styles with the now universal language of jazz? And what are they doing?"

One of the first questions in this field that arose in conversation with Nathalie Ramirez, a professional musician familiar with both traditions, is how to make the rules of the ragas, the musical forms underlying the classical Hindustani and Carnatic traditions – employing up to 72 scales – and their formal and tonal characteristics, fit with the harmony-based language of Western music without producing cacophony. Bearing in mind that a raga is more than a scale and that its ornamental and structural rules, it can be quite difficult to create a musical meshing that both supports its principles and can be governed by those of the harmony of jazz.

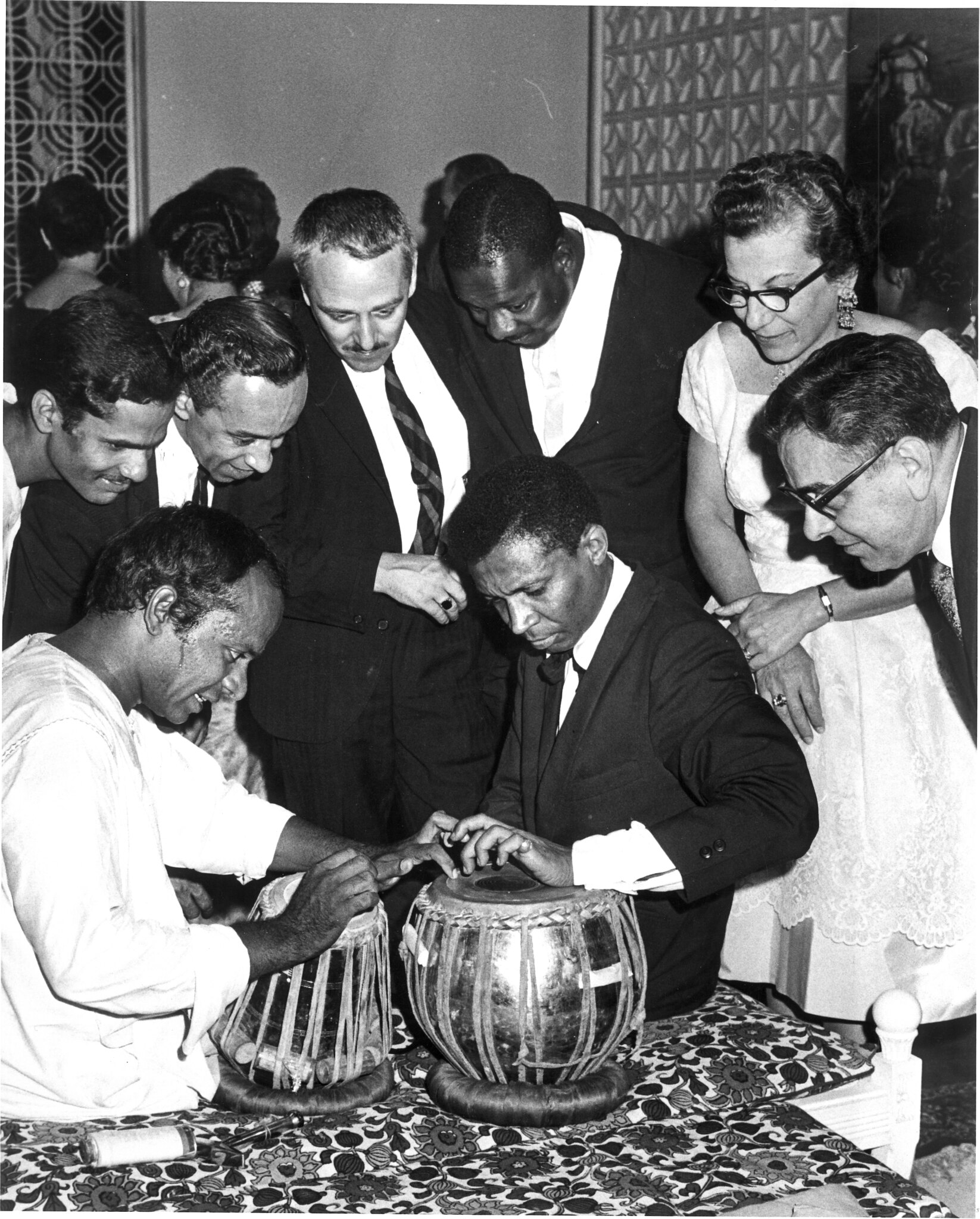

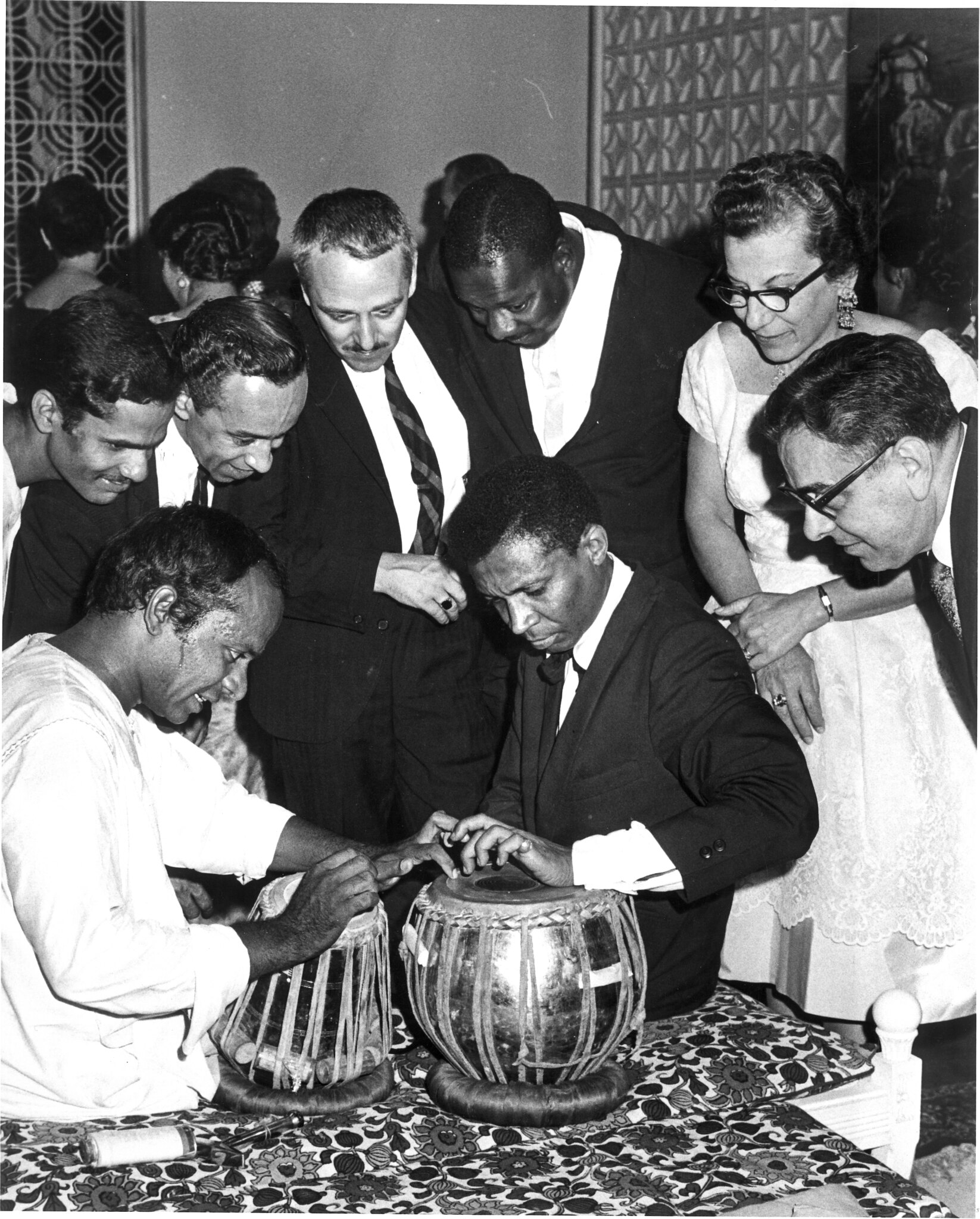

Duke Ellington's orchestra in India with tabla player Chatur Lal | Image courtesy of U.S. Embassy New Delhi

The first musicians who have experimented in a comparable terrain were the musicians of the golden era of Bollywood cinema between the 1940s and 1960s. Some of these musicians were musicians from the jazz orchestras of Bombay that had been the stars of the stages of the luxurious hotels and clubs of the buoyant metropolis. Others were musicians from Gharanas, i.e. schools of Indian classical music, often run by illustrious families who have been involved in music for generations. What is particularly fascinating about this fledgeling film industry that fed writers and musicians is that it created a new and unique style, one of the first to challenge the rules of the ragas, and which gave rise to great popular classics that today, any ordinary Indian can sing or whistle to you with great enthusiasm.

It was in this same metropolis and in this same circle of artists in the film industry that the first work mixing jazz with the ragas of the classical Hindustani tradition was produced in 1968. The resulting vinyl, 'Raga, Jazz Style' is today a coveted object among collectors, as it is a beautiful and fresh rara avis, which has both a Bollywood feel and a sound somewhat reminiscent of Duke Ellington, especially of his works with "oriental" titles. In this work, the equation between "ragistic" ornamentation and Western music is solved in alternative structures created on the one hand by a combo of electric guitar, saxophone, trumpet, piano and drums, and on the other hand, a combo of sitar, bansuri and dholak and tabla as percussion instruments. The jazz-based phrasing finds a diffuse and modified reflection in the melodic journey of the sitar. We are talking about the work signed by, among others, the two Bollywood music directors who worked in duo: Shankar and Jaikishan. On the sitar was Pandit Rais Khan of the Kirana Gharana, one of the most illustrious musical schools of the subcontinent. The jazz phrasing of this work is somewhat limited to qualify as "jazzy", with little use of syncopation or counterpoint, but the result is nonetheless attractive to a listener unfamiliar with ragas and is, therefore, a good introductory work in raga jazz.

Young composer and arranger Sneha Khanwalkar's 'Ab Kya Bataun' ('What do I say now?') written for the film 'Manto' – a 2018 independent film that chronicles the life of writer Saadat Hasan Manto in the years of the subcontinent's independence from the British Empire – is a tribute to this mixed heritage of Bombay culture. The track opens with the vocalist accompanied only by a harmonium and continues with the instrumental accompaniment and some counterpoint trumpet solos that are clearly a nod to the jazz sound that the port city had at the time (the actual instrumentation does not quite correspond to what is visualised in the film).

Since the aforementioned 1968 work, and apart from the experimental journey made by jazz legends such as John McLaughlin, a disciple of Ravi Shankar whose career has often involved the collaboration of tabla player Zakir Hussain, the spiritual music by Alice Coltrane, or those of Ry Cooder with Vishwa Mohan Bhatt, musicians of Indian origin are often divided between Indian musicians with western training and Indian musicians with training in classical or Indian folk music. Few dare to build a bridge to nurture this hitherto unexplored experimentation; some have done so in the field of classical music or indie, but very few have yet done so using the language of jazz.

The big exception is pianist and keyboardist Louiz Banks, the son of Nepalese trumpeter George Banks and one of India’s most accomplished jazz musicians, as described in the Book Taj Mahal Foxtrot by journalist Naresh Fernandes. His son Gino Banks, drummer, is also one of the few active jazz artists in the Subcontinent who also integrates Carnatic and Hindustani traditions in his works. The most renowned piece carrying his name along with respected names from the Indian classical scene and the international jazz scene, is 'Miles From India', a theme released in 2008 as a tribute to Miles Davis.

Another recent work in this hybrid style is signed by an artist from the subcontinent, guitarist Aditya Balani, who, after graduating from Berklee College of Music in Boston, returned to the Indian capital region and founded, together with his brother Tarun, the Global Music Institute. His jazz album 'Answers' begins with a guitar theme entitled 'Bandish'. His style of playing the guitar without frets evokes the sound of the sarod and is inspired by the music of Northern India. The album ends with a richer instrumentation theme entitled 'Quicksand', which although starts with a sound that evokes the American Midwest, gradually introduces ornamental elements typical of South Asian music. This song features guitar, viola, trumpet, bass, drums and piano and is the result of an international collaboration of musicians from four countries including three musicians from India. The album also features a piece titled 'Mirror of Time', whose modal ornamentation has certain flamenco airs.

In a similar line and exploring new grounds is the very recent work of pianist Charu Suri, 'The Book of Ragas'. Born in South India and a resident of New Jersey, Charu Suri was trained in Western classical music and south Indian classical music and later discovered jazz. Most of her musical career has revolved around Western tonal music, but nostalgia for traditional Indian culture marked by its diaspora has taken her further into modal experimentation following in the footsteps initiated decades earlier by Miles Davis and working on a peculiar and totally fresh sound. 'The Book of Ragas' shows the work of a jazz ensemble led by Suri on the piano accompanying Sufi vocalist Apoorva Mudgal who sings traditional Sufi and qawwali melodies, but instead of being accompanied by the usual instruments in that musical tradition, is accompanied by a set of instruments usually used in Western music combos (the album is recorded with vocalist Apoorva Mugdal, while the Carnegie Hall performance was with vocalist Umer Piracha). The contrast between the vocalist's microtones and the tonal "purity" of the piano or cello produces a very original style. The imprint of jazz on Suri's sound also coexists with the influence of Western classical music. Charu Suri's work has a background in the international collaborations made by the most legendary vocalist of Qawwali music, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. But this remains, in general, a very unexplored field.

Charu Suri's work has seen the light of day in the same year that the most ambitious work of pianist Tigran Hamasyan has opened the doors of Caucasian folk music to the jazz repertoire. Tigran Hamasyan is another phenomenon of the "qualified" diaspora of young people from Asian countries who emigrate to the United Kingdom or the New World to study and pursue a career, of which the mother of the current US Vice President is also a good example. This illustrious diaspora includes artists such as Zakir Hussain, resident in the United States, and Anoushka Shankar, in London.

These minorities give colour and diversity to the cultural panorama of the countries where they settle. Their influence in the Great Babylon that the world is today will bring more and more innovation in the sound of jazz.

.

Words: Raquel Rodriguez

Artwork: Sijya Gupta || Image credits: Aditya Balani, U.S. Embassy New Delhi

An earlier edition of the article was originally published in Spanish on Caravan Jazz. It has been translated and updated for Wild City.